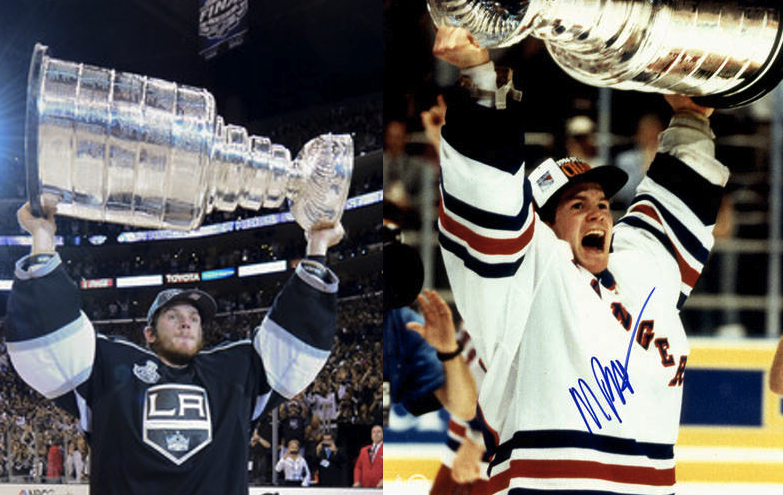

Every Rangers fan who followed the team through that magical 1994 season has a nostalgic affection for Mike Richter. He was the reason myself, and I’m sure countless others decided to put those bulky pads on and have chunks of frozen rubber shot at them. He embodied everything that Rangers fans loved about that team. To say that his career was cut tragically short by concussions is an understatement.

During his peak years, he stacked up against the Brodeur’s, Roy’s and Hasek’s of the league. He was an athletic marvel who made every save exciting and never ceased to amaze with his desire to keep the puck from crossing that red line. As the years have passed and the position has evolved, we have seen a stark decline in goalies that embody the excitement of the game.

The position has become a science, with every move deliberate and each save calculated. Although reflexes and reaction time are still a part of the position, the advances in equipment and technique have made everything look a little too easy. While I feel that this is best for the position, some critics feel that is has sucked the soul out of goaltending. Enter Jonathan Quick.

Quick grew up in Milford, CT (not far from Chris Drury’s Trumbull, CT), and like Drury, grew up a New York sports fan. Quick has listed Richter amongst his influences and it shows in his game. Until Quick’s breakout season last year, his appearances were banished to the 10:30pm East Coast time slot. Due to his emergence as one of the league’s premier netminders, I have had the chance to watch him more frequently. And the more I watch, the more convinced I am that the man is Mike Richter reincarnate.

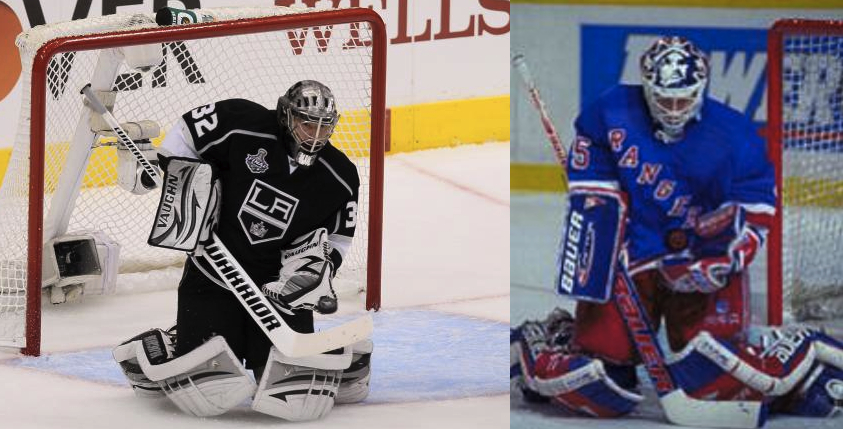

The hallmark of Mike Richter has always been his athleticism and flexibility. Obviously, if you watched even the Stanley Cup Finals, you can see Quick has those qualities in spades. But ultimately, it’s the more nuanced approaches to different situations that really shows Richter’s influence on Quick’s game. What Quick has essentially done is take the baseline style that Richter played in the 1990’s and incorporated those features of modern goaltending into that architecture.

The basic blueprint is this: maintain a balanced and tightly coiled stance, which gives your body the tension to explode in the direction of the incoming shot. The downside is that it makes your overall frame smaller to an incoming shooter, but it ensures that your body is always in the best state to react to the shot.

In order to compensate for the loss in perceived size, a more aggressive style is necessary. Shots from the point are met by the tender standing 3-5 feet outside of the crease. This will enhance your size to the shooter by cutting down distance between the puck and the goaltender. The excess distance from the goal line creates a need for a heightened level of agility, quickness and athleticism in order to recover and maintain quality positioning for subsequent chances around the net mouth.

While both Richter and Quick adhere(d) to it faithfully, Quick has adapted a more modern take on the system. Richter used to accomplish this by basically walking on his skates. He could recover from a down position and skate across the net (or often he would make head first dives, a big no-no in today’s game) and use any part of his body to stop the subsequent shot.

Quick, on the other hand, basically modernizes the theory by utilizing aggressive butterfly slides as his main tool for mobility. What this does is allow him long distance movement while maintaining a seal along the ice, in case of a redirection or a shot that may be aimed against the grain. His backside slides from the top of the crease down to the posts demonstrate a power and precision combination that I, personally, have never seen from a goaltender. Carey Price and MA Fleury come close, but still aren’t at Quick’s level.

Flexibility is a shared trait among these goaltenders as well. Richter’s splits were feats of legend, and while not nearly as useful in today’s game (just from a surface area perspective), Quick knows how to pick his spots with it. Because the butterfly slide technique didn’t really exist during the Richter years, his splits were designed to carry him laterally when he did not have time to utilize any other technique.

Quick tends to use his splits as an extension of his butterfly slide. He will recognize when a play has shifted laterally and use a slide to push himself into the split. This gives him more power than simply flashing the pad out there, while allowing him to travel almost freakish distances while maintaining complete coverage of the lower part of the net.

When examining the photo of the pair’s split techniques, notice the difference in coverage along the ice. Richter’s pads are rotated so the pad faces upwards, while Quick’s are planted firmly face out along the ice.

It takes an absurd athlete to play this type of style in today’s game. It also takes an incredible amount of discipline and dedication to your craft, especially when you consider how controlled Quick’s athleticism is. His landing spots are outlandishly efficient, and he very rarely “scrambles” in the traditional sense, but merely realigns his weight to a position he can use to slide to his next destination. Those two things rarely go hand in hand.

While I was disappointed when the Rangers were eliminated from the playoffs this season, watching Quick gave me a little nostalgic of why I first fell in love with this game to begin with. Richter is still my all-time favorite, and it’s nice to have a little reminder of his impact on the game.

More About:Analysis Around the League Goaltending