Happy Friday, BSB faithful. As promised, Hatrick Swayze has run the gauntlet and earned the right to contribute his learned thoughts in the form of a guest post. Thanks, Hatrick, for a seriously comprehensive piece of work. I hope you all enjoy. Ladies and gentlemen, Hatrick Swayze…

Enter Emerson Etem. [Alliteration. Capitalization. What more could you want? Oh, Carl Hagelin? Too bad for you.] While many are sour over Hagelin’s departure, and for good reason, what’s done is done. All too often in a league with hard cap restrictions, a player’s hard work, dedication and a growth under a franchise ultimately is what forces management’s hand and prices that player out. We’ve seen it with Callahan. Hagelin is the latest victim. Quite honestly, it is a good problem to have. Consider the alternatives: bad draft pedigree, players underperforming expectations, a team meandering in mediocrity. Personally, I’m very content to avoid all of the above. For better or worse, player turnover is the reality of operating in a league governed by a hard salary cap.

As such, it is time we turn our sights to one of our latest acquisitions: Emerson Etem. Unlike Carl Hagelin, who grew up in a Nordic nation, known as an international ice hockey powerhouse with a penchant for strong youth development, Emerson is a born and raised California kid. The Golden state is widely known for surfing, sunbathing, skateboarding and wine touring. Hockey, not so much. Yet still, Emerson, a California native through the age of 14, found his way into the NHL. He would the first to admit that swimming in an Olympic gene pool is as strong a starting point as any. Talented he was. There is a reason, though, that he decided to harness that talent and dedicate himself to hockey as opposed to competitive rowing like his Olympian mother. Had hockey not had a footprint in California, thanks to the Los Angeles Kings (1966) and more recently the Anaheim Mighty Ducks (1993), you could argue Emerson would have never picked up a hockey stick. There is no disputing that many California natives would have never taken an interest in the sport.

Actually, Emerson was very close to making history as the first ever California born and trained player to have been drafted in the first round. Had Beau Bennet of the Pittsburgh Penguins not spoiled this chance to make history by being drafted 8 places before him in 2010 (20th overall), Emerson would have had that distinct claim to fame. But if hockey had not expanded into a non-traditional market, perhaps we would have had to wait even longer for someone to achieve such an accomplishment. As taken from Chris Peter’s article (http://unitedstatesofhockey.com/2013/09/13/hockeys-growth-in-the-united-states-2003-2013/), “Wayne Gretzky’s trade to LA helped lay the foundation and a gigantic hockey boom in the early 1990s, but California has continued on a path to becoming a real hockey state over the last decade. It has the seventh highest hockey-playing population in the country as of 2012-13. The 24,126 registered players last season was an all-time record for the state.” The effect that an NHL presence has on its local market is tangible and often times is directly responsible for fostering the growth of the sport.

It shouldn’t be too surprising that in conjunction with the 36.5% percent ten year player growth which California has experienced, according to USA Hockey, so too has Anaheim’s franchise value as per Forbes magazine. The Mighty Ducks were sold in 2005 for $70 million. In 2014 they were valued at $365 million. That’s north of 500% growth in a similar 10 year timeframe. Normalize that for inflation, and we still have a very impressive growth curve. One, which viewed in hindsight, has me wishing that I would’ve dumped my 401K in, had I not been only 6 years old at the time. Honestly, though, even my piggy bank would have yielded some pretty solid returns. Now for everyone who might be ready to hit Anaheim with the ‘Approval Stamp’ as far as viable hockey markets go, would your opinion change if I told you that Forbes also reported their 2014 operating income, or revenue before interest and taxes, was ($-3.70) million. You wouldn’t be alone if you did decide to start putting that stamp back in your desk drawer. After all, it is common place for many to argue the existence of many “Sunbelt Teams” among others in financial dire straits, Arizona, Florida and Carolina to name a few, for the simple reason that they all usually bleed red ink. All three reported negative operating income for the 2014 season.

Dissenters of financially inept franchises typically build their case on two main fronts: operating losses and low attendance numbers. It certainly makes sense at first glance. There are plenty of viable hockey markets which don’t have a team- why should these unfit cities get to keep theirs? Atlanta moved (again) to Winnipeg and now it’s time to move the others, right? In a vacuum, those arguments and opinions would be correct, however in the real world and within NHL confines there exists a mechanism to allow those in financial turmoil to exist. It is called revenue sharing and it is well worth the cost.

If at this point I’ve lost those of the opinion that hockey is meant for and should only exist in traditional markets, let me reach into my bag of tricks to recapture you’re attention. Name 3 teams all of which exist in cold weather climates, all of which made the playoffs in 2014 BUT STILL reported negative operating incomes for that season. Seriously, try to name them before allowing your eyes to drift right. I mean it- stop reading……six Mississippi, seven Mississippi. Ok go. If you guessed Minnesota ($-5.40 mil), St. Louis ($-6.50 mil) and Columbus ($-15.60 mil) you’d be correct. The State of Hockey, for crying out loud, lost money during a year they had the 8th highest league attendance, 6th lowest average temperature between November and February and enjoyed the luxury of a bolstered bottom line thanks to playoff revenues. The Wild also enjoy the 12th highest metropolitan population among all NHL teams and “has the highest hockey playing population” of 54,951 in 2011-12 according to USA hockey.

To be honest, it is a tough task to try to pin point what makes a hockey market viable. First, what’s viable? Profitability? I think, ultimately, league-wide franchise profitability is the goal albeit an unrealistic one. Let’s have a look at the most bolstered balance sheets among NHL teams as reported for the 2014 year. For this exercise I will use revenue as the metric as opposed to operating income since we are looking to see which markets are capable of generating dollars, not necessarily how dollar savvy each team is managed.

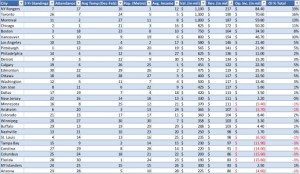

Notes:

5 Year Standings– each team is ranked by the cumulative point totals over the past 5 seasons. I tabulated multiple years of points accumulated in order to avoid one year outliers. Attendance has a bit of a lag effect, so this method should do a better job of avoiding performance driven results.

Attendance– each team is ranked based on 2014-15 attendance numbers

Average Temp (Dec-Feb)– each team is ranked accordingly to title, 1 being the warmest (highest degrees)

Population (Metro)– each team’s population in the greater metropolitan area, 1 being most populous

Average Income– each team is ranked based on income per capita, 1 being most money earned

Valuation, Revenue, Operating Income– all figures provided by Forbes assessment of teams in 2014

Operating Income %- calculation taken to show how big of a piece each franchise is to the pie

The top three teams will surprise no one. Toronto, Montreal and New York are, and have been, the NHL’s titans when it comes to generating revenue. The order, though, certainly points to the on-ice product as a necessary piece of the puzzle. The only reason that the Rangers are able to outdo the Leafs, and the Habs for that matter, in this metric is because our Blueshirts are enjoying what Dave has coined, “our Golden Years”, whilst the Maple Leafs have been in a severe trough- only hosting 3 (Three!?!?!) playoff games at home in the last 10 (Ten!?!?!) years. Holy cow, that’s bad. But it serves as the second point which we could take away from the above table- certain markets are more fit to stomach poorly owned and operated teams and management regimes. This goes without saying. Ask anyone, and they will all tell you that hockey ‘deserves’ to be in Toronto. While I fully agree that despite the recent ineptitude of management in Toronto, I would never advocate for pulling the plug. Chicago is another example, and perfectly exemplifies a pendulum covering its full range of motion. From Bill Wirtz, the owner who refused to televise hockey games, to the closest resemblance we have to a dynasty in modern times (winning 3 Stanley Cups in 6 years), we’ve witnessed the full left tick and the full right tock. Chicago has experienced its downs and its ups. Luckily, for all of us, the franchise has persevered.

Fortunately cities like Toronto and Chicago can withstand the lulls, which typically begin with a poor on-ice product before the problem manifests itself financially. Doesn’t this, though, breed a born-on-third (but act like you hit a triple) mentality? Why shouldn’t non-traditional cities, which aren’t privy to a built in fan base, have a similar, if not longer, leash? I’d argue that they should when the overall 30 team league enjoys overwhelming profits. To me, the name of the game is market saturation. Hockey skates instead of basketballs and surfboards. I am talking about attracting the untapped audience and conjuring talent which hockey otherwise wouldn’t have allured. We all need to understand that penetrating new hockey markets will come with its bruises. To be honest, I’m sure that those in the know, and those who make decisions, do.

This is why one of the bigger triumphs to come out of the latest NHL lockout was a redefined revenue sharing program. Some of the specifics are as follows (black bullets taken from Jamie Fitzpatrick’s article found here http://proicehockey.about.com/od/thenewnhl/a/salary_cap_expl.htm. The hollow bullets are my commentary/ unofficial numbers crunching):

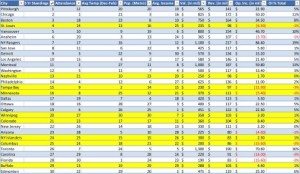

- The top ten money-making teams contribute to the pool.

- 2014/15 top 10 revenue producers: NY Rangers, Toronto, Montreal, Chicago, Boston, Vancouver, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Detroit

- The bottom 15 money-making teams are eligible to collect from it.

- 2014/15 bottom 15 revenue producers: Dallas, Minnesota, New Jersey, Anaheim, Colorado, Winnipeg, Buffalo, St. Louis, Nashville, Tampa Bay, Carolina, Columbus, NY Islanders, Florida, Arizona

- The amount of money contributed by the top ten teams is set by a formula that includes a percentage of overall league revenues and some playoff revenues. The exact number isn’t worked out until the season is over and all revenues have been counted.

- For a bottom-15 team to collect a full revenue sharing check, it must reach at least 80% capacity in home attendance (last year that meant averaging about 14,000 per game) and show revenue growth that exceeds the league average. Missing either threshold means a cut in the share.

- Those who did not meet the attendance threshold: Florida, 11,265 avg, 66.1%; Carolina, 12,594 avg, 67.4%; Arizona, 13,345 avg, 77.9%;

- Those who did meet the attendance threshold: Columbus, 15,551 avg, 85.5%; NYI, 15,524 avg, 94.8%; Tampa Bay, 18,823 avg, 98%; Nashville, 19,854 avg, 98.4%; St. Louis, 18,845 avg, 96.8%; Buffalo, 18,580 avg, 97.4%, Winnipeg, 15,037 avg, 100%; Colorado, 16,176 avg, 89.8%; Anaheim, 16,874 avg, 98.3%; New Jersey, 15,189 avg, 86.2%; Minnesota, 19,023 avg, 106% (full disclosure, I have no idea how one would eclipse 100% attendance, ask ESPN http://espn.go.com/nhl/attendance); Dallas, 17350 avg, 93.6%

- Teams in markets with more than 2.5 million television households cannot qualify for revenue sharing. By my unofficial estimate, that means the Rangers, Islanders, Devils, Flyers, Blackhawks, Ducks, Sharks, Stars, and Kings are ineligible.

- So let’s remove the Devils, Ducks and Stars from the above bottom dwellers.

- This leaves us with the Blue Jackets, Islanders, Bolts, Predators, Blues, Sabres, Jets, Avalanche and Wild eligible to receive full revenue sharing as per the unidentified formula.

Here they are highlighted in yellow (sorted in order of cumulative points over the past 5 seasons):

The above blurb is meant to put practical terms on a theoretical argument. We don’t know all the ins and outs of the revenue sharing formula, so it is meant to serve as a basic study of which teams may or may not be eligible. Who deserves revenue sharing and who doesn’t? To me, the league has it misconstrued. Revenue sharing, in theory, is the best thing to come to a league with intentions of organic grassroots growth. If Toronto can be as bad as it has been for so long, but still rake in $190 million in revenue and operate $70.6 million above break even, you better believe they should be sharing some of that with a team like the Nashville Predators, who earned $98 million and operated a mere $1.7 million in the black. They serve as a perfect example of how good management can persevere in a non-traditional market. Obviously, that is ideal. However, we have all come to understand as fact, that it takes a very savvy franchise and a very apt management to be able to keep a team relevant and competitive for multiple years in a row. The hard cap almost ensures teams will experience peaks and troughs, all in the name of parity. As such, shouldn’t it be unfair to expect markets without built in audiences to be self-sustaining during times when the franchise is in rebuilding mode. No one was knocking Carolina in 2006. But right now they sure as shucks could use a full, not partial, serving of revenue sharing despite the fact they didn’t meet the attendance threshold.

When it comes to revenue sharing, here’s the kicker; its effectiveness is only as good as its application. Markets, such as Colorado, Minnesota and St. Louis have many tangible elements which should breed high attendance and revenue, yet they have trouble harnessing it. For the most part, it isn’t due to on ice ineptitude as St. Louis (thanks to John Davidson), Minnesota and Colorado all finally seem to be on the up and up. But aren’t markets like Florida, Carolina and Arizona more deserving of charity dollars, aka full and complete revenue sharing, in order to give hockey a fighting chance in those markets? I understand the notion of sunk costs and toxic investments, and I am not writing those theories off. However, propping up off the radar and untraditional franchises is well worth the cost when you consider the benefit. And that is what this all boils down to- long term cost/benefit analysis.

The cost: In 2014 the Tampa Bay Lightning Bolts generated the 6th lowest revenue in the league ($97 million), and even worse ran an operating loss of 4th lowest ($11.9) million.

The benefit: In 2015, Steven Stamkos, Ben Bishop and The Triplets lead the same Bolts to a birth in the Stanley Cup Finals, beating our Rangers as the best team in the Eastern Conference.

Take the net operating income of the NHL among all 30 franchises and Forbes tells us that we are $453.5 million in the black. With a pot like that, the haves certainly have the means to support the have nots. What it costs in dollars is well worth the cumulative benefit in terms of talent which will ultimately manifest itself among all 30, soon to be 32 teams.

There is a reason why USA hockey is currently sporting its strongest program ever. The success of the 2010 and 2014 (despite the rough Bronze medal loss to Finland) Olympic teams is no accident. The popularity of the NHL, which allows 76.7% of teams the ability to call this country home, has helped grow the sport within US borders. The growth of the NHL has fueled the growth of hockey, which has in turn helped us amass the largest US born hockey playing talent pool of all time. Just ask Slovenia who their biggest hero is. I’d bet my aforementioned piggy bank (not to be confused with my current 401k) that the answer is Anze Kopitar and his 2014 Olympic heroics which helped put Slovenia’s hockey program on the international map. The domino effect is pretty simple and straight-forward: expose the sport to new markets (for a prolonged period of time), more people take interest, more children find their way to youth programs, the talent pool grows and matures, interest breeds investment (which becomes a self-perpetuating dynamic), fast forward and ultimately Emerson Etem, a California kid is drafted to the NHL in the first round (meaning he is damn good). Had it not been for hockey’s expansion into a once considered non-traditional market, perhaps the young boy pictured above would have never hopped off of that skateboard and into a pair of skates. Thanks to teams like our Rangers propping up teams like Emerson’s former employer in Anaheim, past costs are starting to yield future benefits:

Share:

More About:Business of Hockey Offseason